In this class, students of German 250, "German Film and the Frankfurt School," discuss German-language film, critical theory, and other topics as they emerge!

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Hitler and Cigarettes

I've been reading this French essay that is, in very short, some sort of apogee of smoking. One of the sections mention the humane dimension of the cigarette. Apparently Hitler used to be a big smoker during his youth in Vienna but he suddenly stopped and never smoked again. Hitler said of his old habit that if he hadn't stopped smoking Germany would've never known its present glory. The message the author was trying to convey here is that a cigarette or the deliberate act of doing something that has no other purpose than indulging and pleasure is a tie to humanity, once Hitler gave it up, he gave up his humanity as well.

I hope you enjoyed this little parenthesis!

The name of the essay by the way is Fumer Tue: Peut-on Risquer sa Vie? ( Smoking kills: Do we have the right to risk our lives?)

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Veit Harlan (1899-1964)

He started out working with Max Reinhardt, the famous stage director who worked with so many of the important figures in early German cinema. His first wife, Dora Gerson, was Jewish and died in Auschwitz. His third wife was the Nazi film star Kristina Soederbaum.

His niece, Christiane Susanne Harlan, married Stanley Kubrick.

His film, "Anders als du und ich" (1957), translated as "Bewildered Youth," shows how nefarious men can use modern art and music to seduce boys into a lifetime of homosexuality! Here's a clip (without subtitles):

Re: Consistency in Nazi Propaganda

Susan Sontag

Born in New York, Sontag grew up in Tucson Arizona. She started college at Berkeley (where she had a number of tumultuous lesbian affairs) and then transferred to the University of Chicago, where--after a ten-day courtship(!)--she married her professor Philip Rieff (who you may know as the editor of a number of important English-language Freud editions, such as Dora). They had a baby, David, who is her editor and a writer in his own right. Philip took the family to Brandeis--Susan hated it there! They divorced fairly quickly. At the end of her life, Susan was partners with the famed photographer Annie Liebovitz.

Riefenstahl References

Take a look at Gladiator especially the scene called "Might of Rome." It doesn't seem to be generally available on youtube, but here is a fascinating clip that gives you a sense of the links between the two films:

Similarly, many people have noted connections between imagery in the Star Wars series and Riefenstahl's movie:

Monday, February 27, 2012

Biological Segregation: The Role of Keim in Jud Süß

The emergence of the German Wissenschaft in the 19th century became proof enough for many citizens of who belonged in their nation, and who did not. In Jud Süß, the German nation is unified through a widespread fear of the unknown “other” race and its influence on the common culture.

A nation can be made to be racially defined when biology is used as a category of life. Organic unity, a concept closely tied with a fascist nation, consists of a people united by jus sanguines – by their particular lineage or blood. This biological racism most strongly showed itself throughout history in the German nation in the form of anti-Semitism.

The German nation in Harlan’s film is unified by a generalized fear of the unknown “other” race, in this case being the Jews. What the German citizens fear, more so than the actual Jewish people, is the Semitic influence on the common culture. The popular belief of the German citizens in the film (and indeed the impression left on the viewer) was that the Jews were aiming to completely shift the culture of Germany by expanding their own population and performing continual cultural attacks upon them.

Oppenheimer in particular was credited with disrupting the purity of the German rationale, and provoking the nation into a state of wishing for unification through “One folk, one empire, one leader.” The alarm at the potential influence of alternate races on their treasured German culture propelled the fascist unification forward, prompting citizens of that nation to believe that their noble, virtuous, and honorable lifestyles were direly threatened.

Consistency in Nazi Propaganda

This is a propaganda poster that came out around 1938-1939. The caption reads "The Jewish spirit undermines the healthy powers of the German people."

Clearly, there are a lot of physical similarities between these three posters (however terrible they may be). It kind of amazes me the deeper you look into Nazi propaganda, the more eerily similar you realize the anti-Semitic material was. They clearly had a very specific picture of what they wanted people to imagine Jews as, and ran with it. They also managed to gear it to just about every age group, as well: below I included a page from a horrible anti-Semitic coloring book, as well as a children's book which teaches children to identify Jews by their appearance. If you are interested in seeing more Nazi propaganda, the photo archives at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website have a huge collection of it.

The inscription on the coloring book page on the left reads " Do you know him? Without a solution to the Jewish question there will be no salvation for mankind." The caption on the page from the book "The Poisonous Mushroom" reads "The Jewish nose is crooked at its tip. It looks like the number six..."

Be Prepared!

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Definitely my favorite. :)

Leni Riefenstahl (1902 - 2003)

Leni Riefenstahl was born in Berling on August 22nd, 1902. As a child, she studied painting and took up dancing, quickly becoming famous after her first performance when Max Reinhardt recruited her for the "Deutsches Theater." After a knee injury, she moved on to film and became widely known for her roles in the films »Der heilige Berg« (1926), »Der große Sprung« (1927), »Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü« (1929), »Stürme über dem Mont Blanc« (1930), »Der weiße Rausch« (1931), »Das Blaue Licht« (1932, which she directed) and «SOS Eisberg» (1933). Leni directed a total of eight films in her career, including, notably, Triumph des Willens (1935), named after the Reich Party Congress 1934 in Nuremberg. It received the gold medal in Venice in 1935 and the gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1937. Unfortunately, once the war ended, Leni's career as a film director was effectively destroyed as her films were no longer seen as art but as propaganda.

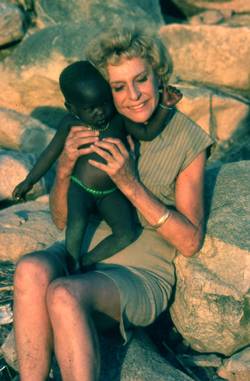

Leni also had an extremely successful career as a photographer, for which she gained fame after her visit with the Nuba. Her photographs were published in the magazines »Stern«, »The Sunday Times Magazine«, »Paris Match«, »L'Europeo«, »Newsweek« and »The Sun«. She also published illustrated books »The Nuba« and »The Nuba of Kau«, which earned her further honors and awards. You can see a bunch of her photos here.

At the age of 71, Leni took up diving and began underwater photography, publishing two more books, "The Coral Gardens" and "The Wonders Under Water," receiving yet further honors and awards for them. In 1987, she published her "Memoirs", after which she continued underwater photography. In 2000 she returned to Sudan to visit her beloved Nuba, but her trip was cut short as she was forced to leave the mountains by helicopter. The helicopter crashed with no deaths and a few injuries, but Leni was taken to a German hospital where they found that she had suffered a number of rib fractures and damaged her lungs. Despite this, she continued her ambitions afterwards and lived to the ripe old age of 101.

Saturday, February 25, 2012

Just taking a moment to embarrass myself.

The Pedal Point

Here's an example of my favorite pedal point at 1:47. Definitely listen to the whole thing to see how it fits in with the rest of the piece, but the pedal point begins at 1:47. It isn't necessarily the STRONGEST example of a pedal point, as the piece is fairly stable and easy to understand harmonically, but I think it's absolutely beautiful. Listen to how stable that bass note is. It's really quite powerful.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mVW8tgGY_w

A dictionary definition: a note sustained in one part (usually the bass) through successive harmonies, some of which are independent of it.

Here's Kracauer's statement again: "Like a pedal point, the cry 'Elsie!' underlies these otherwise unconnected shots, fusing them into a sinister narrative" (220).

What a lovely connection Kracauer makes. This scene's pedal point, the mother's cry, is the stable "tonic" or home key of the story of the murderer, while the independent harmonies, the shots of "Elsie's unused plate on the kitchen table; a remote patch of grass with her ball lying on it; a balloon catching in telegraph wires..." (220) that may seem unconnected are tied together and stabilized.

Friday, February 24, 2012

Der Genitiv

The next film Riefenstahl directed after The Blue Light was not "a documentary on the Nuremberg Rally in 1934"—Riefenstahl made four non-fiction films, not two, as she has claimed since the 1950s and as most current white-washing accounts of her repeat—but Victory of the Faith (Sieg des Glaubens, 1933), celebrating the first National Socialist Party Congress held after Hitler seized power. Then came the first of two works which did indeed make her internationally famous, the film on the next National Socialist Party Congress, Triumph of the Will (Triumph des Willens, 1935)—whose title is never mentioned on the jacket of The Last of the Nuba—after which she made a short film (eighteen minutes) for the army, Day of Freedom: Our Army (Tag der Freiheit: Unsere Wehrmacht, 1935), that depicts the beauty of soldiers and soldiering for the Führer. (It is not surprising to find no mention of this film, a print of which was found in 1971; during the 1950s and 1960s, when Riefenstahl and everyone else believed Day of Freedom to have been lost, she had it dropped from her filmography and refused to discuss it with interviewers.)

Check out those titles! I'm noticing a trend here. Obviously I have not seen all of these films, but I wonder how connected they are in terms of message, feel, and intention.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Michael Jennings

We were very honored today to have Michael Jennings come visit us and give us a little insight to the inner workings of Benjamin and Kracauer. Jennings is an Associated Faculty Member of the Department of Art and Archaeology and the School of Architecture and a Faculty Associate of the Center for the Study of Religion. He sits on the Executive Committee of the Program in European Cultural Studies and the Ph.D. Program in Humanistic Studies. He is the author of two books on Walter Benjamin: Dialectical Images: Walter Benjamin’s Theory of Literary Criticism (Cornell University Press, 1987) and, with Howard Eiland, The Author as Producer: A Life of Walter Benjamin (Harvard University Press, forthcoming in 2012). He also serves as the general editor of the standard English-language edition of Benjamin’s works, Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings (Harvard University Press, four volumes, 1996ff.) and the editor of a series of collections of Benjamin’s essays intended for classroom use, including The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (2007); with Brigid Doherty and Thomas Levin, The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and other Writings on Media (2008) ; and, with Miriam Bratu Hansen, One Way Street (forthcoming in 2012). I think it is safe to say that Jennings knows what he's talking about.

Jennings regaled us today with a peek into the literary beings behind the works of Kracauer and Benjamin, revealing to us that they are actually more closely linked than most give away in that they often shared unpublished work with one another. Jennings suggested that Benjamin was perhaps even more convoluted in his writings and Kracauer was less psychoanalytical and rather more realistic prior to the publications we are familiar with. Of Benjamin, Jennings noted that "[his] earlier writings are remarkably resistant to understanding."

Jennings outlined the evolution of the Kultur section of German papers, which was once separated by a border line (referred to as a Strich) from the top portion of the paper, from articles to the short declarations and statements they became where Benjamin became more public. He also gave us a look inside Benjamin's life, revealing to us that Benjamin was in fact never really Benjamin, but rather wore a different mask for every group of friends, keeping them as separate as possible to avoid overlap, making an allusion to the movie "I'm Not There."

Jennings used a particular word in connection to Benjamin's writings which I have had the opportunity to come across previously in my studies that I would like to elaborate a little on for those who have not yet, as I think it is a fabulous word-- two words, actually. Flâneur is the French word for someone who strolls or takes a walk, but was adopted by philosophers to be someone who wanders the world observing and taking in their surroundings in a passive effort to understand. The term is also used in photography with detached but still aesthetically attuned street photography. Flânerie is therefore the practice of this behavior/lifestyle.

I encourage you to check out Jennings' work here at his Princeton page.

What did you guys think of Michael Jennings' talk? Were there any questions you wish you had asked?

August Sander (1876-1964)

The New Woman

The Soldier

Painters

Brick Layer

Early Photographs

A composition by Daguerre, full of what Kracauer might call "mute objects":

And a photography by Atget, perhaps supporting Benjamin's final claim, "But isn't every square inch of our cities a crime scene?"

Thea von Harbou (1888-1954)

Thea von Harbou was Fritz Lang's companion and fellow artist throughout the 1920s. She worked with him on both Metropolis and M. The married in 1922. Harbou joined the National Socialist party in 1932. She stayed in Germany and in the German film industry, writing the script for the 1937 film Der Herrscher [The Ruler], directed by Veit Harlan and starring Emil Jannings.

Monday, February 20, 2012

Peter Lorre (1904-1964)

In Hollywood, he frequently played slightly unctuous, sleazy, foreign villains--perhaps most notably in The Maltese Falcon and in Casablanca. He was one of the first villains in a James Bond movie.

After the War, he directed a film called Der Verlorene [The Lost One, 1951] in Germany.

Here he is, sending up himself a bit, in the trailer for Mad Love. Lorre's persona was easy to spoof and there are lots of cartoon versions of him.

Fritz Lang's Depiction of a Lynch Mob in Fury (1936)

Lang has a constant interest in the phenomenon of the mob. In Fury (starring Spencer Tracy and Sylvia Sidney, above), he redevelops some of the themes of M, in an American perspective. Once again, you have the mob, thinking it knows what is right; once again, you have a weak state that is scarcely able to provide actual rigorous law and order. And once again, you have a reversal of expectations--while in M, we end up sympathizing with Peter Lorre's character, in Fury, the persecuted outsider becomes bitter and evil and we start feeling sorry for the mob that lynched him.

As in M, we have echoes of fascism--the burning courthouse is like the burning Reichstag.

Here's the lynch scene.

And here's the trailer.

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Influences of Lang's "Metropolis"

According to Wikipedia, Since 1927, two musical theater adaptations of the film have been performed. The first was at the Piccadilly Theater in London in 1989. The most prominent change to the story was anglicizing the German names of the characters: for example, Joh Fredersen became John Freeman, etc. The score was updated and change, and then performed again in 2000 at the Pentacle Theater in Salem, Oregon.

In 2002, Osamu Tezuka's 1949 manga was converted to a feature length anime film, Metropolis. This manga (and film) were said to have been influenced by Fritz Lang's film, but follow a slightly different plot line.

In 2007, producer Thomas Schühly bought the rights to remake the film (no word on where this has gone quite yet).

In 2007, producer Thomas Schühly bought the rights to remake the film (no word on where this has gone quite yet). In addition, a few musicians have pulled inspiration from this film. Madonna's music video for "Express Yourself" pulls influence from the film, as well as Queen's "Radio Ga Ga," which features scenes from the movie in the video.

Link to the Madonna video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GsVcUzP_O_8&ob=av2e

Link to the Queen video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t63_HRwdAgk

Friday, February 17, 2012

Water

<iframe src="http://www.putlocker.com/embed/38127240301DFEBB" width="600" height="360" frameborder="0" scrolling="no"></iframe>

Water, 2005. dir. Deepa Mehta

This is a Canadian/Hindi film that I saw this movie in my senior year of high school, and it is amazing. It is about the caste system in India, and how a widow becomes the lowest caste if her husband dies. This happens to a girl who is less than 10 when her arranged husband dies, and she is forced to become a beggar and prostitute.

I am sharing it in the blog here because the ending of M (where the three women in black say we need to watch our own children) is extremely similar to the ending of this film. I recommend you watch this entire movie, but if not, fast forward to about an hour and 45 minutes into the movie, and watch the scene I am talking about.

Both scenes are really moving, and very well done.

C'mon Krakauer, step it up!

Later, the beggars and criminals become the authority while holding the Kangaroo court. In banding together, they have discovered the common enemy, and decided to persecute him. Lorre's speech, explaining there is nothing he can do to help it calls for some sympathy, and understand. He is sick, but everyone demands his head. One must commend Lang for doing an excellent job capturing the alienation that Hans Beckert is suffering. I feel the theme of alienation and persecution ties very strongly into the Nazi persecution of the Jews during World War II.

In reading Krakauer after having seen M, I was a little bit unimpressed. The only reason I can see for this is the safety of Beckert when the police come and hand him over to an Asylum. Nazis would have sent the mentally insane to a concentration camp. I still disagree with Krakauer not mentioning these themes. Thoughts?

Thursday, February 16, 2012

Fritz Lang

In the late 1950's Lang returned to Germany to continue directing there. In Germany, he remade The Indian Tomb, and directed The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, the final Dr. Mabuse film.

In 1976 Fritz Lang died, a very prolific and innovative director. During his life, Lang was supposedly difficult to work with. During the final scene of M, Lang pushed Peter Lorre down a set of stairs to make Lorre look more battered.

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Maedchen in Uniform (1931)

Sternberg and Dietrich

Although born in Vienna, Sternberg actually spent much of his youth in the US, and began his career in the States. He worked with Emil Jannings in The Last Command (1928). Jannings brought him to Berlin to make the first major German sound film, The Blue Angel.

There he discovered Dietrich, brought her to Hollywood, and made a series of increasingly sexy films with her.

In Morocco (1930), Dietrich cemented her mannish, androgynous image, and gave us one of the great woman-woman kiss scenes in Hollywood history.

The Manns

Thomas's children with his wife Katja are also quite interesting. Erika (1905-1969) and Klaus (1906-1949) were in their 20s in the 1920s and led the glorious glamorous life of the jeunesse dorée in the Berlin of the Weimar Republic.

In the 1930s, they were active against the Nazis. Both emigrated to the United States and served in the military. Klaus Mann's Mephisto, a roman à clef about the actor Gustaf Gründgens, who is portrayed as a typical artist ready to compromise with the Nazis, became a beautiful 1981 film directed by István Szabó.

Monday, February 13, 2012

The Allegory of Folly

While reading Kracauer this morning, a certain section on page 216 caught my attention: the description of Professor Rath as he cockcrows and becomes morally corrupt. I had a bit of a flashback to a research aper I wrote about a work in the Worcester Art Museum, and I thought it might be fun to share some of the main points.

Europe’s “Age of Enlightenment,” known more specifically in the Netherlands as the “Golden Age,” came during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; scientific literature and economic growth led to the creation of a large, prosperous middle class. The newly ‘luxurious’ lives of the bourgeoise during Europe’s Baroque period in the seventeenth century were often a source of uncertainty and even embarrassment to the populace. The solution? Artists created allegorical and still-life moralizing scenes. These paintings “engaged serious questions of moral judgment, temptation, self-definition, and individual responsibility, which confronted those who operated within a world of economic allure and exchange” (Honig, 170).

Paintings from this time centered on material culture, and hidden symbolism pointed to commonplace religious and traditional moral beliefs. One such example is the Flemish painter Quentin Metsys’ Allegory of Folly from c. 1465-1530. Both Dutch and Flemish art was “essentially Protestant in outlook” (Finlay, 52), and incorporated much hidden symbolism throughout, which appealed to the swelling middle class. Such moralizing scenes often used imagery of the Five Senses, the Seven Sins, and vanitas to convey messages to the public, such as the dangers inherent in worldly pleasures. This ties in with the reemerging theme in Kracauer about German’s falling into bouts of sexual excess during times of emotional withdrawl. One example? How the “foolish” Professor Rath was “driven by moral indignation and ill-concealed sex jealousy…into her den; but instead of putting an end to the juvenille excesses, he himself succumbs to the charms of Lola Lola…” (Kracauer, 216).

Folly, as a common theme throughout Europe but particularly in Antwerp, was a frequent topic in Baroque paintings. Metsys made use of the method of “instruction through ridicule” when convincing his audience of the merits of being righteous in his painting. Folly, as seen here, is shown as a combination between the two common yet contrasting representations of himself: a stupid or “mentally handicapped” character identified by the “stone of folly” lump on the forehead, who was generally seen in courts for entertainment purposes; and the witty and satirical comedian who dresseed as a fool to make fun of society’s own follies. The cockerel coming out of his head was used as a common symbol of ‘the fool’. Remind you of anyone? Professor Rath in The Blue Angel also played the fool, and with his “wonderful imitation of cockcrowing,” eventually led to his ultimate “humiliation” and characterization as a “madman.”

Rich with symbolism, Allegory of Folly alludes to the insults directed to and coming from fools, which may lead one to the conclusion that Metsys was hinting at society’s duplicitous nature. Folly’s traditional “fool’s costume” in itself is even ripe with meaning. The ears of an ass, belled cap, red belt, and staff, all enhance the comical nature of the fool, and invite the viewer to poke fun at the character’s expense. (Ahem!) Prof. Rath was also laughed at, during his cock-crowing performance, and it came at the expense of his sanity and his character.

Folly’s staff, also know as a marotte, contains a protruding miniature figure of none other than himself; the carved effigy of the fool mimics his model, detectable by the matching cap. The marotte’s figure is shown in the profane act of pulling down his pants, which reiterates the derogatory disposition of the fool, while simultaneously insulting society itself against its own follies. Again, back to Professor Rath: He originally looked down upon the rest of society, especially his students, for their immoral dispositions. And yet, he himself became immoral in the same light. A juxtaposition became present of his degraded position and his superior mindset.

Folly holds his forefinger to his lips, which seems almost to contradict the satirical nature of the cretin, given that silence during the time that Metsys painted this work was widely considered to be associated with wisdom and educated persons. However, not to stray too far from the theme of contradictory façades of both Folly and Flemish society, Metsys incorporated a phrase “Mondeken toe” (translated to mean “keep your mouth shut”) immediately adjacent to the raising finger. Rath, too, kept silent for quite a bit of The Blue Angel. Long stretches of time passed before he addressed his students, and even when he had something to say, he used few words. Possibly an allusion to his educated status.

The subject in Allegory of Folly is unsightly and misshapen. The over-exaggerated deformities – a hunched back, crooked nose, lumped forehead, and crinkly, decrepit skin – repels the audience, while at once intriguing them, and making them unable to look away. The allure of such a painting lends into the theme of the audience’s own vanity, also associated with the moral instruction of this composition. The association here to the professor? Remember how his appearance changed over the years, and how he eventually became the clown. The grotesque, wrinkly-foreheaded, large-nosed, scarred clown. I think that the same elements of his version of the fool that were present in Metsys’ painting are what drew his hometown audience in.

Examples of human folly in other such paintings include the succumbing to sin and the Bacchic indulgence in revelry and sexual appetite.

Sorry for the length – I really tried to cut it down to just the relevant points.

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Metaphor Time with the Clown

So, obviously, when Rath himself became the clown, I had a fit. Metaphor time!

Madly curious, I searched the lovely JSTOR for other opinions, and came across this article by Geoffrey Wagner, which answered a lot of my questions.

He writes

“From the outset, in fact, the professor is haunted by the figure of the clown in the background, for he, the man of ideals, is himself a clown in the world of The Blue Angel.”

A-ha! So he became the clown as Lola, the 1930s rendition of Pandora, slowly destroyed him. This brought me back to thoughts from Ashley’s speech, in which she talked about the film Der Büsche der Pandora from 1929, in which Lulu’s sexual ambition and thoughtlessness destroyed lives around her, and eventaully her own. Lola was a bit luckier though, and escaped with her life.

Rath was insecure about the continued sexual nature of Lola’s work, and he was ultimately destroyed by that. The last lines that Lola sings in the film (no subtitles, unfortunately) are translated as “when a man burns in lust, who can find him salvation?”

Symbolic, no?

Wagner also makes the connection between Rath’s burning lust and his ripping off of the calendar days with a hot curling iron. So that explains the smoke then. And it only got smokier throughout the years, signifying his growing jealousy.

Let’s tie it all together, shall we? So because Rath was reduced to a sad, empty version of himself via Lola’s sexual prowess, and was forced to return to his hometown in such a state, he became the essential clown – the fool. He was humiliated, eggs were cracked onto his forehead, he watched as his wife hooked up with another man. He was ridiculed by all those he used to think below him. This degradation reminds me of the human perception of aura concept from Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” – he was happy when he believed himself a man of culture, not a fool. He was still cultured, but because of his new job as a literal clown, in combination with his lack of money and being supported by woman, he was a fool. His aura was corrupted.

The article connects the film to Kracauer’s beloved chaos theory with the following quote:

Thus at the beginning, when the professor first enters, the cabaret is shown as chaotic, almost surrealistic, with its whirling clouds, miasmic veisl, and shifting backdrops; at the end, when he is part of it, it is steady, and brutal in its clarity.

Marlene Dietrich

“A strange combination of the femme fatale, the German Hausfrau and Florence Nightingale" is how the film director Billy Wilder described this remarkable woman. Marlene Dietrich (1901-1992) was a German-American actress and singer who moved to Hollywood in 1931 and maintained her long career by continually reinventing herself.

Born in Schoeneberg, Germany, Dietrich originally wanted to be a concert violinist but when that dream failed, ventured onto the Berlin stage in the early 20’s during which time she appeared as a chorus girl with vaudeville style entertainments and acted in silent films. In 1929 she was cast as 'Lola-Lola' in The Blue Angel, directed by Joseph von Sternberg. Her performance brought her international fame and resulted in her move to Hollywood and subsequent contract with Paramount Pictures. According to Wikipedia, Paramount sought to market Dietrich as a German answer to MGM's Swedish sensation, Greta Garbo. Going on to star in six more films directed by von Sternberg, Dietrich’s glamour and exotic looks were legendary and made her one of the highest paid actresses of the era.

Dietrich was both and iconic image on screen and in the fashion world. She was bisexual and created her own style with her seductive look and androgynous wardrobe. In regards to her image, film critic Kenneth Tynan said, "Her masculinity appeals to women and her sexuality to men." She famously stated once, "Don't ever follow the latest trend, because in a short time you will look ridiculous, don't follow it blindly into every dark alley. Always remember that you are not a model or a mannequin for which the fashion is created." While she wore beautiful and outlandish costumes on screen, in real life she often wore comfortable menswear. Dietrich was the first Hollywood actress to wear trousers in public and helped make them more acceptable for women.

Dietrich’s life was described as “more dramatic, more unpredictable and more colorful than any Hollywood scenarist could invent.” While she married assistant director Rudolph Sieber, and the couple had a child, Marie Elisabeth Sieber, Dietrich maintained an unending string of affairs throughout her career (almost all of which were known to her husband!). Her male lovers included John Wayne, Jean Gabin, Maurice Chevalier and Generals Patton and Gavin. Her lesbian love affairs included that with Marcedes de Acosta, the socialite who had also been partners with Greta Garbo.

- Dietrich refused a lucrative contract from Nazi officials to return to Germany as a foremost film star in the Third Reich and instead chose to apply for U.S. citizenship in 1937.

- Among her many conquests, Dietrich slept with Joseph von Sternberg, the very man who helped bring her to fame.

- After much success in the first half of the decade, she was labelled "Box Office Poison" in the late 30's along with others like Fred Astaire, Joan Crawford and Katherine Hepburn.

- Her legs were insured by Paramount for 1 million dollars!

Friday, February 10, 2012

Benjamin's Aura and Popular Culture

Treats in Store: Werner Herzog

In the meantime, though I'll give you something as German as Kaesepaetzle and Bier: Werner Herzog on chickens. Watch it!! It's only 40 seconds, and you'll love it.

And once you're done with that, then I guess you're going to have to watch Werner Herzog on "Where's Waldo?" (Although I don't think this actually is Werner Herzog.... but then who "actually is" Werner Herzog?

Thursday, February 9, 2012

What Makes it German?

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940)

Benjamin died in the Pyrenees fleeing from Nazis. It is generally thought that he committed suicide when caught on the border, but the film Who Killed Walter Benjamin (2005) argues differently.

Louise Brooks in Pabst's "Pandora's Box"

Perhaps one of the purest embodiments of the New Woman, Louise Brooks (1906-1985) was an American star who moved to Berlin in the 1920s to star in a number of films by Georg Wilhelm Pabst (1885-1967). Here's a fun tribute to her, with lots of stills.

In Pandora's Box (1929), based on shocking plays by Frank Wedekind, she plays Lulu, perhaps the greatest femme fatale ever!

The movie features one of cinema's first lesbians, the Countess Geschwitz, and includes a charming dance between the two.